The Caracal (Caracal caracal) is among the most widespread small cats in the world. However, knowledge of its conservation status and ecology in its Asian range countries is minimal and severely outdated. Consistent reports however do originate from India, Israel and Iran. The Caracal has interestingly been considered rare in India for a little more than three centuries. In 1671, President Gerald Aungier, British East India Company Officer who became the second Governor of Bombay, was presented a Caracal by the Mughal General Diler Khan in exchange for a pair of English greyhounds. Even back then, Aungier was made aware of what a rarity the Caracal was in India and thus arranged to have it shipped back to England. Naturalists have continued to comment on the Caracal’s rarity in India since then to the present day, with some even going as far as to suggest that it is on the verge of extinction.

However, little is known of the Caracal’s ecology in India during the last four centuries. In order to understand whether the species has indeed experienced a decline in India, Dr. Dharmendra Khandal and Ishan Dhar of Ranthambhore based NGO, Tiger Watch and Dr. G.V. Reddy, recently retired as Head of Forest Forces for the state of Rajasthan conducted a study on the Historic and current extent of occurrence for the Caracal in India published in the most recent special issue on small wild cats in the Journal of Threatened Taxa. This is the culmination of two yearlong effort, which involved the review of several books and journals as well as sourcing and interacting with individuals from all walks of life who might have crossed paths with this elusive animal in India.

Cover photo of December month edition of Journal of Threatened Taxa

Despite the Caracal’s rarity, it has an extraordinarily rich history with humans in India. The Caracal was prized for its ability to hunt birds mid-flight. The vernacular name, Caracal, originates from the Turkic word Karakulak, which literally translates to ‘black-ear’, drawing emphasis on its long black tufted ears. In India, the Caracal is vernacularly known by its Persian name, Siyagosh, which also directly translates to ‘black-ear’. A fable from the Sanskrit text, the Hitopadesa, focuses on a small wild cat named Dirgha-karan or ‘long-eared’ preying on a bird’s chicks. This is the closest we come to what could possibly be a Caracal in Sanskrit literature. In fact, it was only in 1953, that a Sanskrit name, sas-karan or ‘rabbit like ears’ was proposed as a part of a broader attempt at formulating Sanskrit nomenclature for the fauna of India, Myanmar and Sri Lanka following the Linnaean system of classification.

The Caracal was first used as a coursing animal in India during the Delhi Sultanate. In the 14th century, Sultan Firoz Shah Tughlaq established a ‘Siyah-Goshdar Khana’ for the maintenance of his vast collection of coursing Caracals. The Third Mughal Emperor Akbar also used the Caracal extensively for coursing. It was during the Akbar’s reign that the Caracal also began to be represented in illustrated simplified Persian illustrations of Sanskrit, Arabic and Turkic texts literature such as Anvar-i-Suhayli, Tutinama, as well as Persian classics such as the Khamsa-e-Nizami and Shahnameh. The Caracal’s extensive use historically as a coursing animal and the lack of a Sanskrit name led to some questioning whether the species is indigenous to India at all. However, in 1982, a scientist with the ZSI, Mranomoy Ghosh re-examined a skull fragment purported to have been the earliest fossil of a domestic cat in India. The fragment had been collected from Harappa in 1930 and had been erroneously identified as that of the domestic cat. Ghosh reviewed the skull and discovered that it in fact belonged to a Caracal. This fossil record is India’s oldest Caracal finding, dating to 3000-2000 BC and establishing that the Caracal was present in the Indian subcontinent during the Indus Valley Civilization.

The vernacular name, Caracal, originates from the Turkic word Karakulak, which emphasis on its long black tufted ears. (Photo: Dr. Dharmendra Khandal)

However, it is possible that the Caracal’s rarity can be explained by landscape-level anthropogenic changes that have occurred in India since at least 1880. Examining changes to the Caracal’s extent of occurrence in India is a step towards understanding how such change could have impacted the species. In this endeavour, the authors of the study attempted to collate all records of the Caracal in India from the start of recorded history until April 2020, map its historical extent of occurrence and evaluate any changes to its present extent of occurrence. An endeavour made all the more challenging by the prevalence of coursing Caracals historically as well as the at times frustratingly elusive behaviour of wild Caracals.

The authors search entailed an extensive review of literature from the onset of recorded history to the year 2020, spanning almost four centuries. This included the writings of naturalists, zoologists, natural historians, historians, forest officers, gazetteers, chroniclers, erstwhile royalty and army officers. An examination of Caracal specimens deposited at the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), Zoological Survey of India (ZSI), the Natural History Museum in London, private trophy collections in India and other museums was also conducted, along with open-ended interviews with forest officers and biologists who observed the Caracal in the field and people who provided photographs. The authors collated and categorized reports according to their reliability in the following manner: A.) confirmed reports based on tangible evidence like photographs, specimens including animal carcasses or body parts that can be accessed currently; B.) confirmed reports based on direct sightings of live or dead individuals, specimens submitted to museums that are no longer accessible or missing, photographic reports that are no longer accessible, destroyed or missing; C.) confirmed reports that indicate Caracal occurrence through species specific information which includes species description and the provision of distinct vernacular names; D.) unconfirmed or questionable reports without any accompanying description, photos or erroneous description.

Indeed 33 reports were considered ‘unconfirmed’ as they were questionable or erroneous. Misidentification with the Jungle Cat is also an ever -present challenge, with erroneous reports continuing to be perpetuated to this day, simply because they have been published. The authors strictly did not include any reports of captive or coursing Caracals as their wild origins were unknown unless explicitly stated. In addition, a regular camera trapping exercise carried out by Tiger Watch’s Village Wildlife Volunteers in and around the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve since 2015 was also drawn upon. For this exercise, camera trapping is carried out by trained pastoral herders monitoring tigers outside the Tiger Reserve. All reports gleaned from this search were geotagged onto maps to determine the historical and current extent of occurrence areas.

In India there are only two potentially viable populations of Caracal, one in the Ranthambore Tiger Reserve and other in the Kutch district of Gujarat. (Photo: Dr. Dharmendra Khandal)

The authors collated 134 reports starting from the year 1616 until April 2020. The Caracal was historically present in 13 Indian states and in 9 out of 26 biotic provinces. Since 2001, the Caracal’s presence has been reported in the three states of Rajasthan, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh and four biotic provinces, with only two possible viable populations in the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan and the district of Kutch in Gujarat. Prior to 1947, the Caracal was reported from an area of 793,927 km2. Between 1948 and 2000, the Caracal’s reported extent of occurrence in India decreased by 47.99%. From 2001 to 2020, the reported extent of occurrence further decreased by 95.95%, with current presence restricted to 16,709km2, less than 5% of the Caracal’s reported extent of occurrence in the 1948 to 2000 period and just 2.17% of the period before 1947.

In Rajasthan, there have been a total of 24 Caracal reports since the year 2001. 17 of these reports are backed by photographic evidence. 15 of which are from Ranthambhore, along with a photograph taken from Sariska in 2004 and a camera trap picture from the Keoladeo Ghana National Park in Bharatpur in 2017. However, from 2015 to April 2020, the Village Wildlife Volunteers obtained 176 camera trap pictures of Caracals from 6 locations in and around the Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve. Their camera trapping efforts even conclusively established the Caracal’s presence in the district of Dholpur in Rajasthan. This is the largest repository of photographs for the Caracal in India and quite possibly its entire Asian range. With Ranthambhore being one of two possible viable populations in India, the Village Wildlife Volunteers will be indispensable to any forthcoming conservation intervention concerning the Caracal in India. Since 2001, there have been only 9 photographic Caracal records from Kutch and no photographic records from Madhya Pradesh.

Camera trap photo taken by Village Wildlife Volunteers (PC: Tiger Watch)

It is possible that the Caracal might still be present but underreported in states like Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and the eastern parts of India. Targeted surveys will be required to further verify and adjust the putative reduction in range size established by this study. With the exception of a handful of studies, there has been virtually no contribution to the knowledge of Caracal ecology in India in the 21st century. Surveys on Caracal population size, reproduction, mortality, home range sizes, and prey dynamics are the need of the hour. A review of just how the categorization of land as a wasteland, impacts the Caracal, which is a scrub dwelling species is also urgently required. Long-term studies focusing on the movement patterns of Caracals to determine and establish wildlife corridors that are suitable to connect the remaining fragmented population units are equally essential. The authors of the study hope to inspire conservationists to join the fight to prevent the Caracal from becoming extinct in India.

Authors:

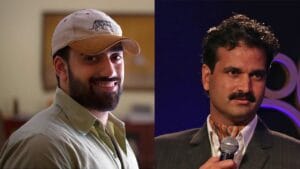

Mr. Ishan Dhar (L) is a researcher of political science in a think tank. He has been associated with Tiger Watch’s conservation interventions in his capacity as a member of the board of directors.

Mr. Ishan Dhar (L) is a researcher of political science in a think tank. He has been associated with Tiger Watch’s conservation interventions in his capacity as a member of the board of directors.

Dr. Dharmendra Khandal (R) has worked as a conservation biologist with Tiger Watch – a non-profit organisation based in Ranthambhore, for the last 16 years. He spearheads all anti-poaching, community-based conservation and exploration interventions for the organisation.

हिंदी में पढ़िए

i m interested to protect these elusive wild cats. thank you for the vast informations.this article will help indians to know about the rare cat in our country thank you soomuch for this wonderfull article.waiting for an another caracal study reports.please send me the volume of threatened taxa magazine of caracals.hope we can protect them.kindly arjun m