Just how ruthless British sporthunters could be in their relentless pursuit of India’s wildlife during the Raj can be discerned from the writings of Sir William Rice. William Rice was a lieutenant in the 25th Bombay Regiment, and described in his hunting memoirs, his role in 156 grand hunts over a span of 5 years, during which he killed 68 tigers and injured 30, thus hunted a total of 98 tigers, killed only 4 leopards and injured 3, therefore hunted a total of 7 leopards, and killed 25 bears and injured 26, and thus hunted a total of 51 bears.

Rice felt that readers might suspect exaggeration on his part, and duly named 7 officers as eyewitnesses to his bloody handiwork. Most of the aforementioned animals were hunted in the areas of Gandhi Sagar, Jawahar Sagar, Rana Pratap Sagar, Bijoliyan, Mandalgarh, Bhainsrorgarh in Rajasthan. If you are a wildlife lover, you are unlikely to not want to curse Rice after reading every page of his memoirs. However, if we read history whilst flowing in a river of emotion, then we are liable to miss out on the real picture of that era, and the anecdotes penned by William Rice are very relevant to tiger conservation today.

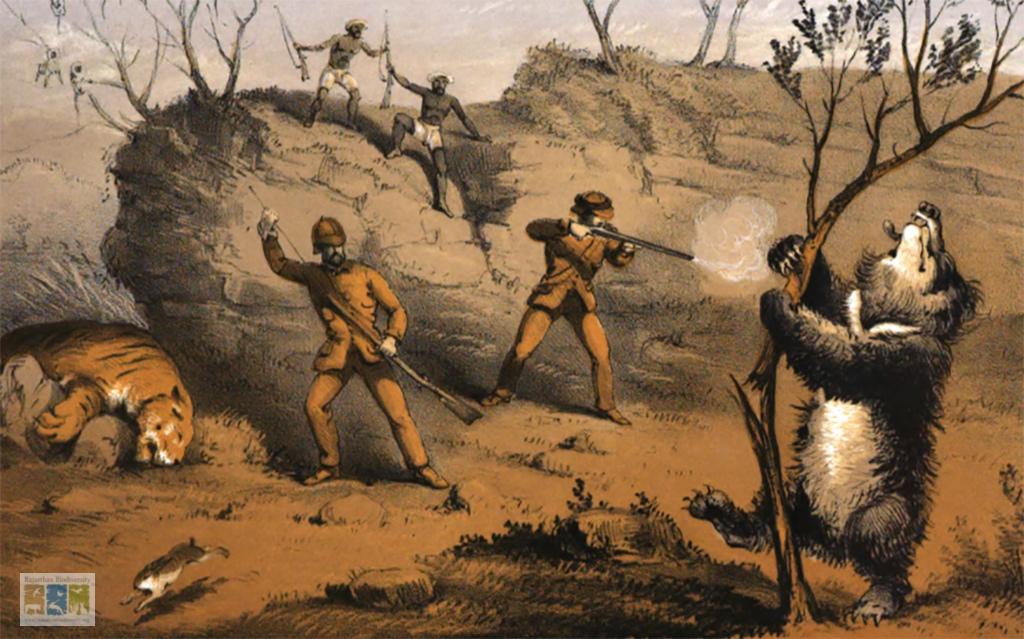

‘Jaat panther charging’ from Tiger Shooting in India : Being an account of Hunting Experiences on Foot in Rajpootana, During the Hot seasons from 1850 to 1854 by Sir William Rice. By panther, Rice means leopard

Rice once wrote that he was puzzled that he did not find a large animal to hunt in the forest of the village of Ambha, located on the other side of the Chambal river in front of Bhainsrorgarh after spending five days there. He was then informed that some pastoralists had recently poisoned 2-3 tigers with arsenic. It seems that back then, between the years 1850-1854, to poison a tiger for lifting cattle was a very common practice.

‘Order of procession following up a wounded tiger’ from Tiger Shooting in India : Being an account of Hunting Experiences on Foot in Rajpootana, During the Hot seasons from 1850 to 1854 by Sir William Rice.

At present, it is not easy to guess just how common retaliatory killings of tigers by poisoning are. In the last decade, at least 5 tigers have been poisoned to death in Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve. These 5 tigers were confirmed cases of poisoning by government laboratories. We don’t know how many such cases have not come to the fore. According to these data reports by Tiger Watch – https://tigerwatch.net/status-of-tigers-in-ranthambhore-tiger-reserve/, it is known from studying the disappearance data of Ranthambhore tigers during the last 10 -11 years, on average at least 3 tigers go missing every year. However, in the last year 2020-21, this number has alarmingly climbed to 12- https://tigerwatch.net/the-missing-tigers-of-ranthambhore-2020-2021/. It is unclear just how many of these missing tigers are the result of negative human intervention.

‘Panic at Deypoora’ from Tiger Shooting in India : Being an account of Hunting Experiences on Foot in Rajpootana, During the Hot seasons from 1850 to 1854 by Sir William Rice.

William Rice described that when the tiger hunted the cow, the pastoralists swore revenge, and when the tiger was away from the kill, they made some long vertical incisions in the dead cow’s back and filled them with arsenic. Along with this, Rice also wrote that the powder of a red coloured berry also used to serve as poison in the same vein.The ‘ berries’ were in all likelihood, of the tree Strychnos Nux-vomica, locally known as Kuchla, a common, and much-favoured poison in those days. Neither poison has a distinct smell, so tigers would ingest it while eating large chunks of meat, only to die soon after. Nowadays, irate livestock owners poison cattle kills by injecting them with insecticides.

Even Ramsingh Mogiya, a member of the Mogiya traditional hunting tribe, and resident of Laxmipura (outside Ranthambhore Tiger Reserve), lamented that this was the method being used to destroy animals these days, and that it is unfortunately on the rise. It seems that some hunters, whether it was William Rice or members of the Mogiya tribe, are saddened when confronted with wildlife being destroyed in this way.

References:

- Rice, W. (1857). Tiger-shooting in India: Being an account of hunting experiences on foot in Rajpootana, during the hot seasons from 1850 to 1854. Smith, Elder and Co., London, 219pp.

Authors:

Dr. Dharmendra Khandal (L) has worked as a conservation biologist with Tiger Watch – a non-profit organisation based in Ranthambhore, for the last 16 years. He spearheads all anti-poaching, community-based conservation and exploration interventions for the organisation.

Dr. Dharmendra Khandal (L) has worked as a conservation biologist with Tiger Watch – a non-profit organisation based in Ranthambhore, for the last 16 years. He spearheads all anti-poaching, community-based conservation and exploration interventions for the organisation.

Mr. Ishan Dhar (R) is a researcher of political science in a think tank. He has been associated with Tiger Watch’s conservation interventions in his capacity as a member of the board of directors.

हिंदी में पढ़िए