Today, to stay away from antiquated first aid treatments for snakebites is repeated ad infinitum (and with good reason). The mainstays of these purported treatments involved tying tourniquets above the bites, and making incisions with knives to ‘bleed’ the venom out. But where did these treatments come from? Who first recommended these methods?

The man responsible was Joseph Ewart, a British surgeon. Ewart had been in the employ of the British East India Company since 1854. Ewart was attached by the company to the Mewar Bhil Corps. The Mewar Bhil Corps is a police corps first established by the East India Company along with Mewar State in southern Rajasthan. The corps were raised to maintain peace in what was then an inaccessible area, and to bring Bhil youth into the ‘mainstream’. Since the year 1841, this corps has consistently worked in southern Rajasthan, and still exists today as a paramilitary force under the Rajasthan Police.

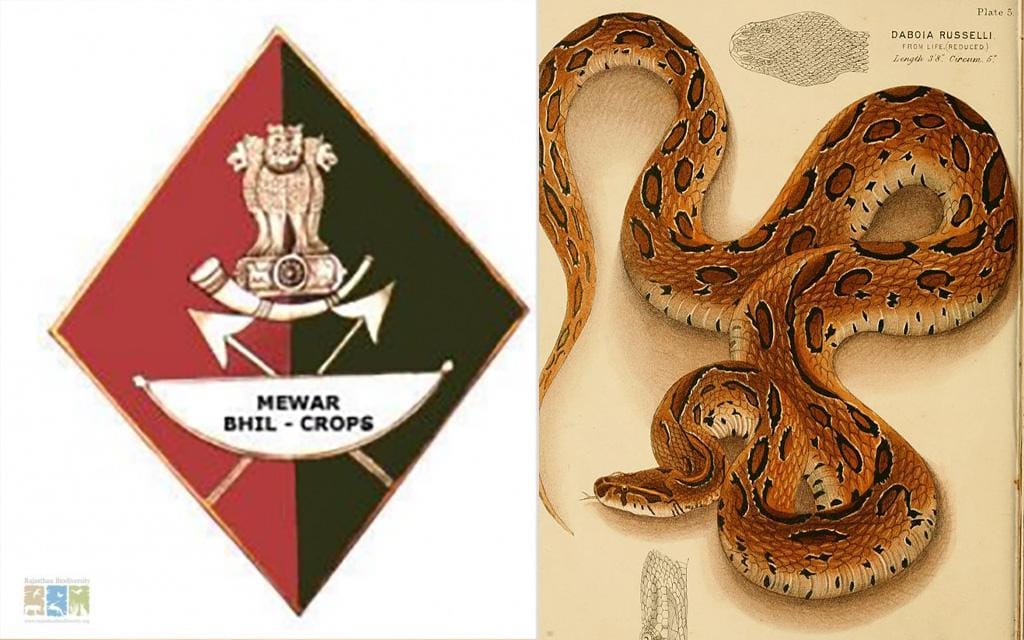

An illustration of a Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii) from The Poisonous Snakes of India. Along with cobras and kraits, the Russell’s viper is responsible for the lion’s share of snakebite fatalities in India.

The Bhil youth recruited into the corps are very intrepid and expeditious. Their work ethic is also notable, historically, when a lathi (long stick serving the purpose of a baton) charge was ordered to disperse a mob or riot, the personnel took the order to heart, and accordingly marked their men. They then enthusiastically chased their targets with their lathis held aloft, and pursued them all the way to their homes, at times even after delivering a sound beating. Therefore, whenever they were given their orders, they were explicitly told what to do, as well as what not to do. Historically, the Mewar Bhil Corps made significant contributions in pacifying bandit-affected areas – the notorious Mir Khan was caught by them.

The insignia of the Mewar Bhil Corps, now a paramilitary unit under the Rajasthan Police.

In the part of Rajasthan where this corps is located, there is also a dense jungle, which today constitutes the Phulwari ki Naal Wildlife Sanctuary. As a result, their personnel regularly fell victim to snakebites. Their British officers worried in turn. At the time they weren’t aware of the different kinds of snakes found in India, let alone how to recognize, and avoid them.

The Poisonous Snakes of India was first circulated among British officers in India, only to be republished and brought back into public consciousness by Himalayan Books in 1985 with unforeseen consequences.

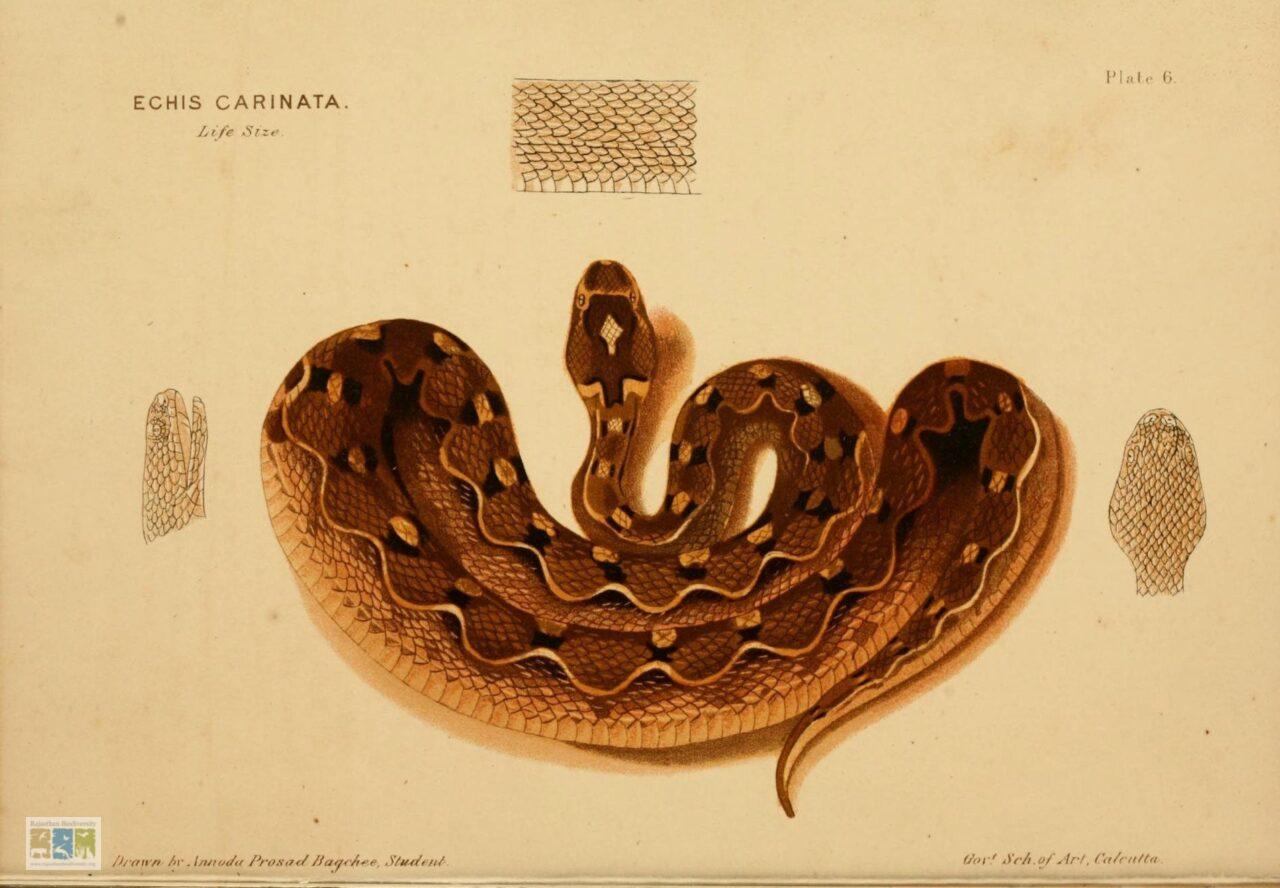

This is precisely why Joseph Ewart was attached to the corps. During his time with the corps, he observed many snakebite cases, which he studied along with hypothesizing purported treatments. He did whatever little he could without antivenom, on the basis of his personal experiences. He eventually wrote a book titled The Poisonous Snakes of India, published in 1878, in which there are also uncannily accurate illustrations to help readers identify venomous snakes. Ewart also expounded on various purported treatments for snakebites in the book.

A life size illustration of a saw-scaled viper (Echis carinatus) from The Poisonous Snakes of India.

When first published, only a 1000 copies of the book were printed and distributed to British officers in India. Since there are only a few surviving copies, they have now become prized collectors’ items for Raj nostalgists. A surviving copy of the book is currently worth INR 1 lac.

Times have proven the purported first aid methods mentioned in the book to not only be dangerous to snakebite victims, but also fatal i.e. making an incision on the bite site and bloodletting, cauterising the bite site with a hot iron bar and burning hot embers, tying tourniquets etc. (None of these measures work, and are NOT to be implemented in the event of a snakebite, please read more –https://rajasthanbiodiversity.org/snakebite-challenges-in-rajasthan/). It is equally important to remember that this book was written before the invention of antivenom.

An illustration of a spectacled cobra (Naja naja) from The Poisonous Snakes of India.

In all likelihood, this book would have faded into obscurity, had it not been republished by Himalayan Books in 1985, and this otherwise beautiful book came back into circulation in India, along with all its antiquated information. The simultaneous resurgence of old, dangerous and redundant first aid methods for snakebites is no coincidence, and highly problematic. While this book is certainly of great relevance to historians and collectors, when dealing with a snakebite, it is best to consign Ewart’s prescribed methods to their rightful place in the annals of history.

Authors:

Dr. Dharmendra Khandal (L) has worked as a conservation biologist with Tiger Watch – a non-profit organisation based in Ranthambhore, for the last 16 years. He spearheads all anti-poaching, community-based conservation and exploration interventions for the organisation.

Dr. Dharmendra Khandal (L) has worked as a conservation biologist with Tiger Watch – a non-profit organisation based in Ranthambhore, for the last 16 years. He spearheads all anti-poaching, community-based conservation and exploration interventions for the organisation.

Mr. Ishan Dhar (R) is a researcher of political science in a think tank. He has been associated with Tiger Watch’s conservation interventions in his capacity as a member of the board of directors.

हिंदी में पढ़िए