The Strange Tale of Two Missing Bats in Rajasthan

We often fail to recognize that the knowledge of the biodiversity of a location in India, be it a single locality or region, results from a cumulative process of documentation stretching back centuries. Most of this knowledge stems from the written works of European naturalists and explorers in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This information was then passed down from one author to another in a chain through citations, with very few ever questioning the veracity of some reports. Rajasthan was no different, despite being the scene of considerable scientific field exploration after independence in 1947.

As a result, certain mysteries and loose ends in information continue to bewilder us, particularly when we decide to step out of the realm of charismatic fauna and take a closer look at other species.

For instance, why has a bat species, Tickell’s bat Hesperoptenus tickelli (Blyth, 1851), not been recorded in Rajasthan for over a century? Did it go extinct? Or is something else afoot? Could there have been an error in documentation by an early naturalist that has gone unnoticed all these years?

Furthermore, why was the possibility of another species of bat being found in Rajasthan, the small mouse-tailed bat Rhinopoma muscatellum Thomas, 1903 suddenly raised in 1997 when there has been no evidence of it ever being found in Rajasthan?

Answering these questions demands a fresh look at historical sources and even some contemporary ones.

Col. Samuel R. Tickell (1811-1875), after whom Tickell’s bat and multiple bird species are named. Tickell reportedly collected the type specimen for this species in Chaibasa, Jharkhand, in 1842, which is why the species is named after him. (Public Domain Image)

- Tickell’s Bat

A look at the encyclopedic Bats of the Indian Subcontinent (1997) by P.J. Bates and D.L. Harrison reveals that Tickell’s bat was reported from Nasirabad in Rajasthan-“INDIA: Rajasthan: Nusserabad.”

Strangely, they did not include Nasirabad or any other place in Rajasthan on the accompanying distribution map for this species and do not explain why. Perhaps they doubted this report.

The book they rely on for this information is Mammalia (1888-91) by William Thomas Blanford. Now where did Blanford get his information from? Blanford referenced all the available literature on this species at the time and wrote that it was found in, the “Peninsula of India (Nusserabad in Rajputana; Bombay; Chybassa; Jashpur, Sirguja in SW Bengal)”.

A look at the literature referenced by Blanford reveals that it was in G.E. Dobson’s Catalogue of Chiroptera in the British Museum (1878), that we first see specimens of this species recorded from “Nusserabad, India”.

Let us consider that this is the first mention of a location in India called “Nusserabad” being connected to this species. Dobson DID NOT write that the Nusserabad being discussed here was in Rajasthan or any other specific locality. Dobson also did not provide other details that could have helped us trace where these specimens were collected from, such as the name of the collector nor when they were collected, except that the British Museum received them from East India House.

The remaining sources Blanford referenced for this species do not mention Tickell’s bat being collected from anywhere in Rajasthan; therefore, it was Blanford who first connected Rajasthan to this species. Adding Rajputana to the locality information (Nusserabad) appeared to be based on nothing more than an assumption by Blanford.

Now, what could have caused Blanford’s assumption? After all, there were at least six localities named “Nasirabad” in British India, so why would he add Rajasthan (or then Rajputana) to this ambiguous locality?

As we have seen earlier with three other bat species, it was likely the connection of Captain W.J.E Boys to the town of Nasirabad in Rajasthan. Now, who was Captain W.J.E Boys?

Captain W.J.E Boys was a cavalry officer with the British East India Company, but more importantly, he was a very well-known and highly prolific collector of specimens. As mentioned in an earlier article, Nasirabad in Rajasthan has a long history as a cantonment town.

Despite not being named in the literature connected to this species, it is more than possible that Blanford assumed that Captain Boys was the collector and that therefore the specimens were collected in Nasirabad, Rajasthan, in the absence of a specific locality and collector identity in the information provided in Dobson’s catalogue. Such assumptions have been made before with other species and there is no other explanation for why Blanford made this assumption.

After Blanford, many authors perpetuated the unfounded assumption that Tickell’s bat was recorded in Rajasthan, which skewed the distributional record of this species for a very long time.

No evidence of the presence of this species in Rajasthan has ever been found despite many field surveys and exploration in the state.

2. Small Mouse-tailed Bat

This case is even stranger than that of Tickell’s bat because it takes place in modern times and contemporary scientists’ works.

Coming back to the Bats of the Indian Subcontinent, Bates and Harrison wrote in 1997 that this bat has possibly been recorded in a place called Genji in Rajasthan: “Tamil Nadu: Genji (doubtful record, restricted to Coromandel coast by Van Cakenberghe & de Vree (1994) but possibly Genji in Rajasthan)”.

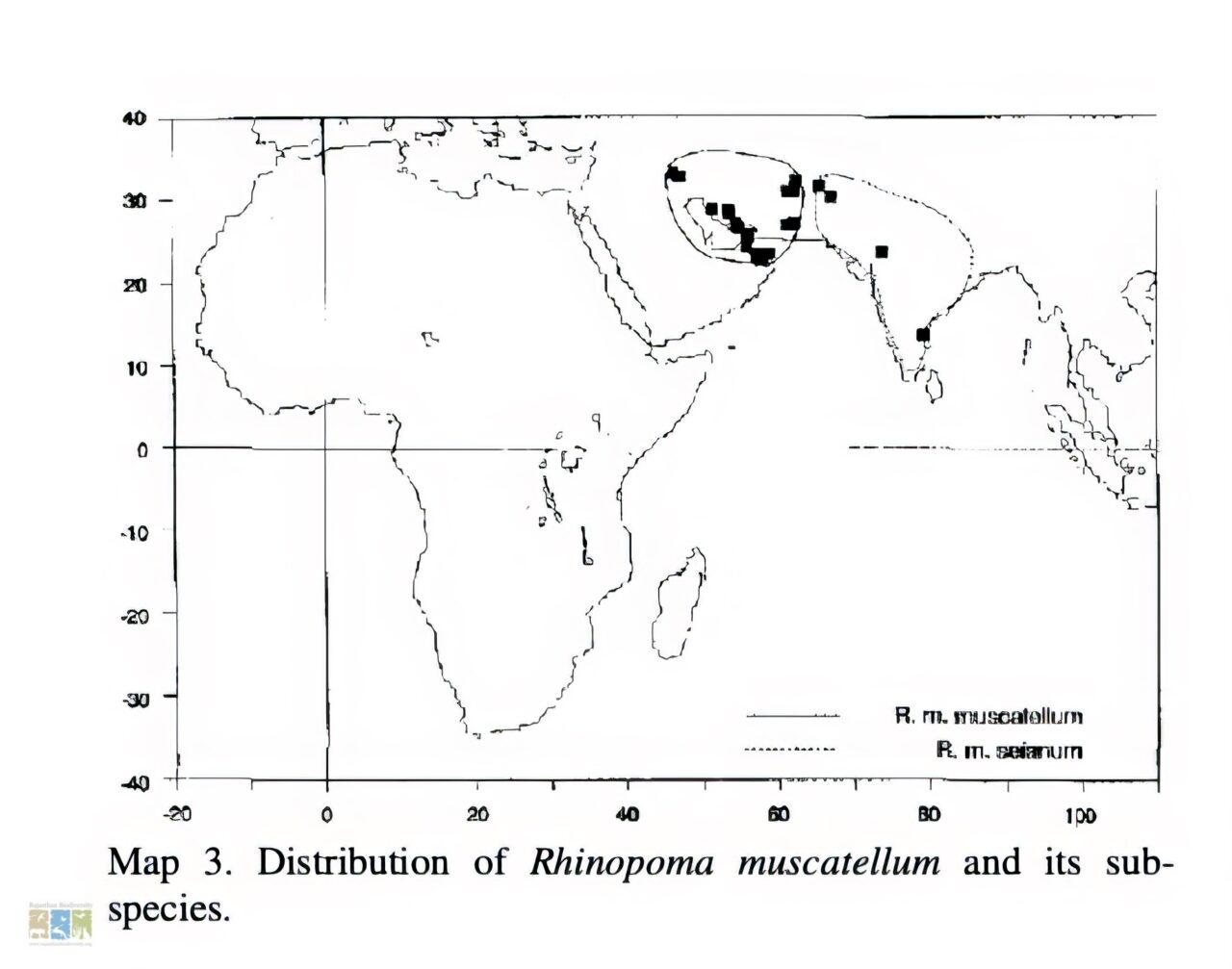

They were sceptical, however, as they do mention the record is doubtful for India. The map provided by Bates and Harrison nevertheless marks both Genji in Rajasthan and a spot on the Coromandel coast in Tamil Nadu with a “?”. Which unfortunately inadvertently gives credence to the report.

It is possible that when Bates and Harrison viewed this report alongside other reports of this species from Afghanistan and Pakistan, a locality in Rajasthan might have seemed like a natural part of its distributional area.

However, we must now look at the source that Bates and Harrison relied on to understand how the possibility of this species being found in Rajasthan was raised in 1994 and never before.

In a 1994 paper titled “A revision of the Rhinopomatidae DOBSON 1872, with the description of a new subspecies”, Victor Van Cakenberghe and Frits de Vree wrote that specimens of this species were probably collected from a place named Genji on the Coromandel coast.

Their information was based on documents that were with specimens which are stored in the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. Despite possessing this information, they were strangely unable to find a locality named “Genji” on the Coromandel coast.

They did, however, find a place named “Genji” in Rajasthan, but still concluded that the specimens of the small mouse-tailed bat were from south-eastern India while merely noting that “Genji” also existed in Rajasthan.

Despite their conclusion, they still marked Genji in Rajasthan on their distributional map for the species, thereby unfortunately lending credibility to the possibility that the specimens could have been collected from Rajasthan.

Map by Van Cakenberghe and de Vree (1994), which also shows Genji in Rajasthan as a locality for the small mouse-tailed bat even though they concluded that the single Indian locality report for this species was from Southeastern India.

The collector of these specimens was Maurice Maindron, who was believed to be in the areas of Pondicherry and Karikal around September, 1901, about the same time the specimens were captured in “Genji”. Both areas are within the vicinity of the Coromandel Coast.

While Van Cakenberge and de Vree were unable to locate “Genji” in the area in 1994, we (Dharmendra Khandal, Ishan Dhar and Shyamkant S. Talmale) found a locality near the Coromandel coast in Tamil Nadu spelt “Gingee” in 2023.

Although this seems very hard to believe, the cause of this mystery ultimately boiled down to a spelling inconsistency.

It is important to remember that many early European naturalists were inconsistent with the spellings of Indian localities. We have already seen this with Nasirabad/Nusserabad in the previous case. Therefore, “Gingee” on the Coromandel coast in Tamil Nadu is probably what Maurice Maindron meant by “Genji”.

So yes, even a spelling inconsistency can completely skew a species’ distributional record if the authors are not careful or not mindful of geography.

However, the strange tale of the small mouse-tailed bat does not end there. There is good reason to believe that not only was the species not recorded in Rajasthan, but it may never have been found in India.

After he was employed by the Museum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, Maidron travelled almost uninterrupted for the next 25 years. In addition to India, he visited other parts of the small mouse-tailed bat’s global range, such as “Arabia,” in 1896, before his third visit to India in 1900-1901, which is when the specimens were reportedly collected from “Genji.”

This could mean that the specimens were possibly collected from somewhere in West Asia, such as the Persian Gulf, where the species is still found today, and were perhaps mislabelled afterwards. Errors such as these by curators have been documented previously, such as in the British Museum.

Fortunately, the possibility of this species being found in India was not articulated beyond Bates and Harrison, as subsequent authors on Indian bats have omitted this species from their works.

This case shows that not only can assumptions and errors by historical authors skew the distributional records of species, but contemporary authors are quite capable of similar errors if they do not account for the inadequacies of historical sources.

For more details about these two cases, read this paper authored by Dharmendra Khandal, Ishan Dhar and Shyamkant S. Talmale in the Journal of Threatened Taxa.

Cover Image generated by Gemini Advanced AI

Mr. Ishan Dhar (L) is a researcher of political science in a think tank. He has been associated with Tiger Watch’s conservation interventions in his capacity as a member of the board of directors.

Mr. Ishan Dhar (L) is a researcher of political science in a think tank. He has been associated with Tiger Watch’s conservation interventions in his capacity as a member of the board of directors.