We often feel a sense of joy when a colorful butterfly flutters around our garden or home. Now imagine — what if hundreds or even thousands of such butterflies appeared all at once? What a spectacular sight that would be!

Such a phenomenon is observed every year in the fringe areas of Ranthambhore, particularly in the pasture lands of Sherpur and Khilchipur. Here, amidst open grounds dotted with Capparis decidua (ker) and Capparis sepiaria (heens) shrubs and tiny wildflowers, waves of white-yellow butterflies suddenly begin to appear. They have black-tipped wings and veins which are distinctly visible. The males are generally paler, with clean black lines, while the females show more prominent black patterns on their forewings and are slightly larger in size — naturally, as they must nurture eggs in their abdomens (Smetacek, 2012).

This spectacle lasts for about one to one and a half months.

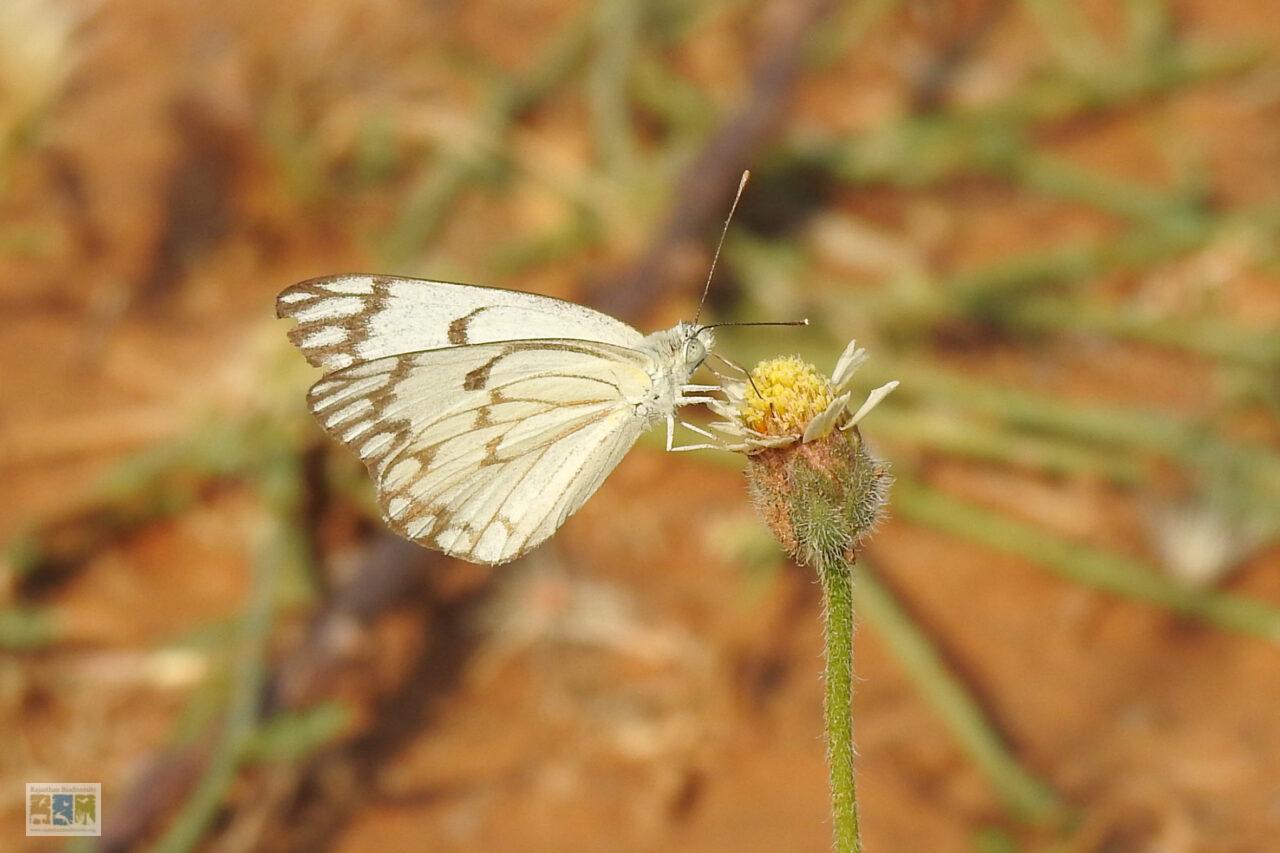

The Pioneer butterfly was most frequently observed on the flowers of Brahma Dandi (Oligochaeta ramose). (Photo: Praveen)

These are Pioneer Butterflies (Belenois aurota), also known as Caper Whites. Their numbers suddenly swell to such an extent that nearly every shrub seems occupied solely by this one species. In a 10×10 square meter plot, we counted between 500 and 1000 individuals — a remarkable and recurring annual sight.

Where Do They Come From?

A question arises — where do these butterflies suddenly emerge from in such large numbers? Are they long-distance migrants, as suggested by entomologists Moore (1890s) and Bingham (1905) during the British era? Or are they reappearing locally as part of a life cycle?

We believe that these butterflies are not migrants, but residents that emerge from dormancy with the first showers of April, transforming into their adult form as they emerge from pupae.

At first glance, the white-flowered Santari (Convolvulus prostratus) appears to be the most abundant plant in this area. (Photo: Dr. Dharmendra Khandal)

From the Pages of History

Frederic Moore, working in British India, was the first to describe this butterfly in detail in his series Lepidoptera Indica. He observed that they appear suddenly after the monsoon and swarm around caper plants. Later, Charles Bingham described their massive swarms moving in a south-west to north-east direction — seemingly in parallel with the advancing monsoon.

What We Observed

Contrary to the descriptions given by Moore and Bingham, we did not observe these butterflies during the monsoon. Instead, we saw them in large numbers around the shrubs of Capparis decidua (Ker) and Capparis sepiaria (Heens), and among tiny ground flowers, soon after the rainfall in April. On a single Heens shrub, as many as 100–150 butterflies could be seen.

This rainfall, which occurs during April–May, is locally called “Dongde”. It is distinct from the monsoon that follows the summer and the “Mawath” that occurs during the winter. Dongde is sudden and unpredictable, often consisting of just one or two brief showers. Though short-lived, this life-giving rain transforms the dry landscape by providing abundant food and favorable conditions for many species — especially the Pioneer butterfly, for whom it appears to be a key ecological trigger.

The life cycle of the Pioneer butterfly is closely linked to plants of the family Capparaceae. Its main larval host plants are Capparis sepiaria (Heens) and Capparis decidua (Ker) (Arora & Mondal, 1981). In this region, the butterflies were mostly found on these shrubs, which are also the plants they prefer for laying eggs.

Physically, Pioneer butterflies are delicate and poorly adapted to extreme heat. Their activity begins at dawn and generally ceases by 9 a.m., after which they seek refuge under shrubs to escape the intense sunlight. While they are swift fliers, their flight is limited in range — fast, fluttering, and close to the ground. They mostly hover around host plants and nectar sources, suggesting they do not travel long distances. Moreover, since Dongde rain is localized and brief, it does not render the entire landscape suitable for long-range dispersal or migration.

Based on these observations, we inferred that the Pioneers are likely resident butterflies, completing their life cycle locally and reappearing seasonally with the first Dongde showers.

Detailed Behavior and Ecology

Scientists suggest that Pioneers prefer wide, open flowers for nectar. They are commonly seen on Tridax procumbens, Lantana camara, Calotropis, and Ziziphus (Kunte, 2000; Kunte et al., 2021). However, in our systematic early-morning field studies in Ranthambhore, we observed them feeding on a different set of local plant species — starting with the very first rays of the sun.

At a glance, the white-flowered Convolvulus prostratus (Santari) appeared most abundant, sprawling across open fields. But when we conducted a 10×10 sq. m plot survey, we found that the highest number of flowers — around 500 — belonged to Oligochaeta ramose (Brahma Dandi), making it the butterfly’s preferred nectar plant. This was followed by Lepidagathis trinervis (Trinadi) with approximately 300 flowers, while Santari had just around 100.

In addition to these three major plants, Pioneers were also seen feeding on:

- Echinops echinatus (globe thistle)

- Argemone mexicana (prickly poppy)

- Evolvulus alsinoides (Vishnukrant)

- Solanum xanthocarpum (yellow-berried nightshade)

- Launaea procumbens (wild lettuce)

Pioneer butterflies nectaring on a variety of flowers — Brahma Dandi, Santari, Khoon-Rokni, and Oont-Kanteli. (Photo: Dr. Dharmendra Khandal, Praveen)

These butterflies begin their day quite early, around 6:00 a.m. Initially, they feed on O. ramose flowers, then shift to the newly bloomed Santari (still tinged with purple), and later to other available flowers.

Between 8:30 and 9:30 a.m., most butterflies can be seen basking in the sun near shrubs of Capparis, Ziziphus, and Heens, especially on Santari flowers. This basking helps regulate their body temperature — a critical behavior for ectothermic insects.

Mating activity also begins in the cool morning hours, typically between 6:00 and 8:00 a.m., lasting up to two hours. By around 10:00 a.m., most activity ceases. In the afternoon, they seek shade under shrubs like Capparis and Ziziphus. While some butterflies stay active throughout the day, a noticeable rise in activity is observed again around 4:00 p.m. At night, they rest on the eastern side of shrubs — likely to avoid the last rays of the hot western sun and to warm up quickly at sunrise.

In the evenings, most butterflies are in flight, while some females are seen sitting still on host plants, wings open, seemingly waiting for a male. When disturbed by nearby movement, females raise their abdomen — a behavior we interpreted as a sexual signal or mate-choice display.

Later, we confirmed this “abdomen lifting” is a post-mating signal, indicating that the female is no longer receptive and thereby avoids further mating attempts.

After mating, the female Pioneer butterfly raises her abdomen — a clear signal that she is no longer receptive to further copulation. (Photo: Praveen)

Egg Laying and Mate Guarding

To ensure the next generation, females lay eggs singly or in small clusters on the underside of host plant leaves. These eggs are oval, upright, pale cream to yellowish in color, and show fine ridges (Sharma & Khan, 2022). They are typically placed in shaded areas on a single leaf to ensure protection and moisture.

Interestingly, in our observations, all eggs were laid on the upper surface of leaves — especially on those with a slight upward curl along both edges. This deviation from earlier descriptions suggests adaptive variability.

During this period, males often engage in mate guarding — staying close to the female after mating to prevent other males from attempting to copulate again. We frequently observed males actively chasing away other intruding males.

The Pioneer butterfly typically lays its eggs on the upper surface of leaves, often selecting those that are gently curved along both edges. (Photo: Praveen)

Ecological Role and Interactions

Ecologically, the Pioneer butterfly plays a dual role — while it completes its life cycle by heavily feeding on the leaves of host plants like Capparis, it also exerts pressure on these plants, making it locally significant as a herbivore and potential pest.

At the same time, it becomes a critical resource for other species. One notable ecological interaction we observed involved social spiders, which appear to specialize in preying on Pioneer butterflies. These spiders build dense webs near or on Capparis and Heens shrubs — an intelligent strategy given these are the very plants where Pioneers congregate. In a single web, we documented dozens to hundreds of trapped butterflies, highlighting the butterfly’s central place in the local food web.

This relationship illustrates the complexity of predator-prey dynamics in the ecosystem and shows how the abundance of one species can significantly influence others.

Based on our observations and the ecology of the region, it seems highly likely that the Pioneer butterfly is a resident species, reappearing each year in response to regional climate cues — particularly the early Dongde rains of April-May.

This butterfly is more than just a seasonal visitor. It is a sensitive indicator of climatic patterns, a pollinator, a herbivore, and a prey species — a small but significant player in the intricate web of life. In the context of climate change and shifting land-use patterns, documenting species like the Pioneer, understanding their population dynamics and ecological relationships, is more important than ever. It may well hold clues to the future of ecological resilience.

Cover Image: Dr Dharmendra Khandal

Interesting article 🌿🐛🦋

Very informative. Never thought there is so much to know about butterflies. Thanks to the writers for putting great efforts in bringing the knowledge forward.

Quite interesting & informative…👏🦋🦋🦋