Butterfly Park – Amberi, Udaipur

Butterflies are diurnal, non-biting, non-stinging, six – legged (3-paird) insects heaving 2 pairs of wings for flying. Both, butterflies and moths are collectively included in order Lepidoptera. Body of members of this order is covered with colored scales. They have four stages in their lifecycles namely, egg, caterpillar, pupa and imago or adult. Their caterpillar stage is a leaf eating stage; pupa, a fasting stage and adult represents a sucking phase of the life cycle. Mouth parts of an adult butterfly are formed for sucking and are in the form of a coiled tube or proboscis.

Order Lepidoptera is further divided in to two sub groups namely, Rhopalocera and Heterocera. All the butterflies are included in Rhopalocera while all the moths are classified in Heterocera taxa.

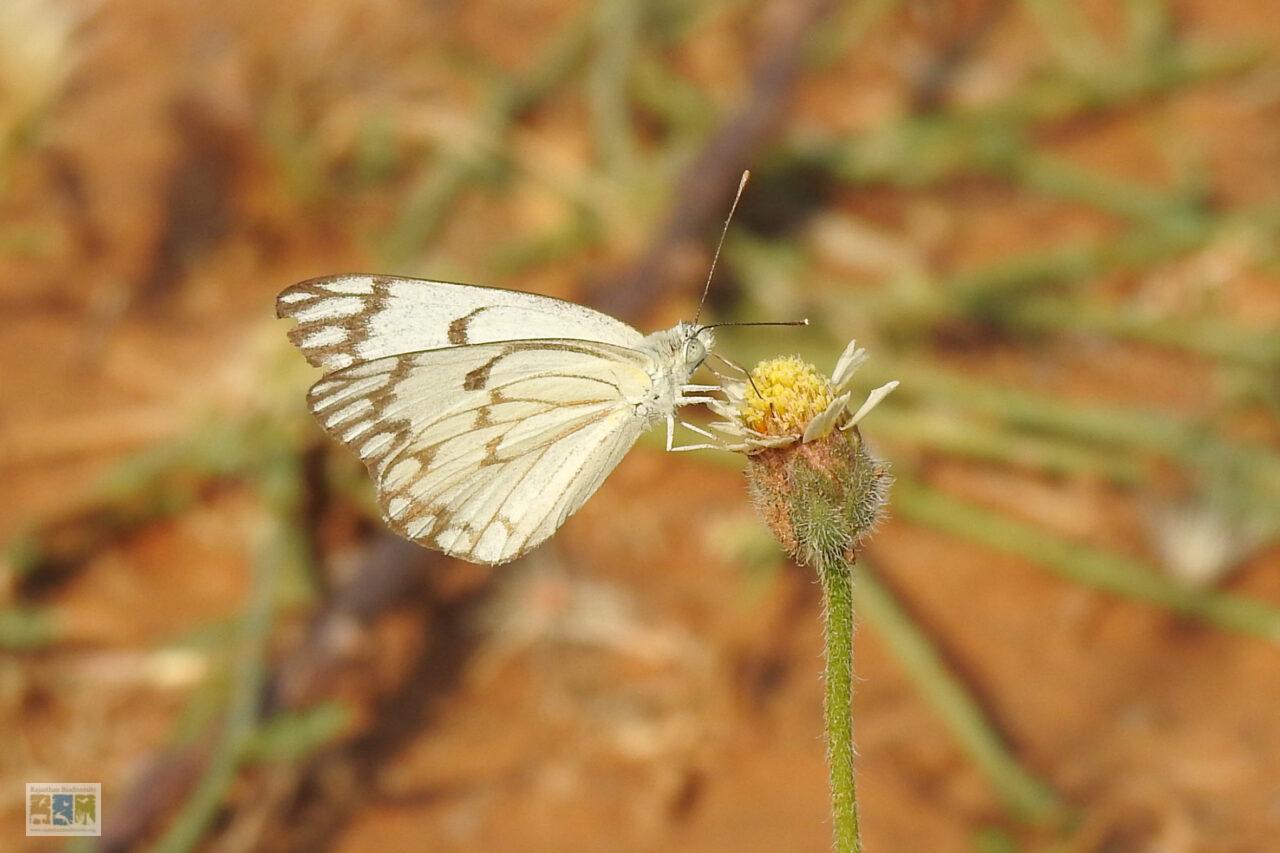

A biodiversity park has been developed in the Amberi Forest Block by the Forest Department Rajasthan known as “Mewar Biodiversity Park”. It was inaugurated on February 26, 2016. To create mass awareness about the butterflies, a butterfly park was developed inside the “Mewar Biodiversity Park, Amberi, Udaipur”. It was inaugurated on June 24, 2024. So far 83 species of the butterflies have been recorded in this butterfly park. For the benefit of tourists coming to visit the butterfly park, a field guide has been developed by the park authorities to make butterfly identification easy. Many larval host and nectar plants are naturally growing in and around the butterfly park (Fig-1&2). Besides naturally growing pants a large number of larval hosts and nectar providing species have been planted to enrich the habitat quality of the park. Monsoon and summer are the best period to visit the park. Few or all four stages of the butterflies namely, egg, caterpillar, pupa and imago can be seen in this park after limited efforts only.

Figure 1: Gateway of Butterly Park, Amberi, Udaipur

Many walk ways have been developed in the butterfly park. Using these paths, visitors can reach at different corners of the park very easily. The micro habitat and micro climate of the park is very congenial to different species of butterflies and moths. Suitable mud puddling points are also developed to meet out the biological needs of the butterflies.

Figure 2: Vegetation of Butterfly Park Amberi

A list of the butterflies, so far seen in the Butterfly Park Amberi and their larval hosts are shown below in table 1:

TABLE 1: BUTTERFLIES AND THEIR LARVAL HOSTS CONFINED IN AND AROUND THE BUTTERFLY PARK AMBERI

S. No. | Name of butterfly species | Name of host species useful as larval host | |

Common Name | Latin Name | ||

1. | Common rose | Pachliopta aristolochiae | Aristolochia indica, A. brateolata |

2. | Crimson rose | Pachliopta hector | Aristolochia indica |

3. | Lime | Papilio demoleus | Aegle marmelose, Citrus limon |

4. | Common Mormon | Paplilio polytes | Aegle marmelose, Citrus limon |

5. | Tailed jay | Graphium Agamemnon | Polyalthia longifolia, Annona squamosa |

6. | Common jay | Graphium doson | Polyalthia longifolia, Annona squamosa |

7. | Spot swordtail | Graphium namius | Miliusa tomentosa |

8. | Common grass yellow | Eurema hecabe | Pithecellobium dulce, Cassia tora |

9. | Spotless grass yellow | Eurema laeta | Cassia pumila |

10. | Small grass yellow | Eurema brigittav | Cassia pumila |

11. | Common emigrant | Catopsilia pomona | Cassia siamea, C. fistula |

12. | Mottled emigrant | Catopsilia pyranthe | Cassia siamea, C. occidentalis |

13. | Psyche | Eptosia nina | Capparis sepiaria |

14. | Pioneer | Belenois aurota | Capparis sepiaria, C. decidua |

15. | Little orange-tip | Colotis etrida | Capparis decidua, Maerua oblongifolia |

16. | White orange-tip | Ixias marianne | Capparis sepiaria, C. decidua |

17. | Yellow orange-tip | Ixias pyrene | Capparis sepiaria |

18. | Common gull | Cepora Nerissa | Capparis sepiaria, C. decidua |

19. | Common jezebel | Delias eucharis | Dendrophthoe falcata |

20. | Western striped albatross | Appias libythea | Maerua oblongifolia, Crateva spp. |

21. | Large salmon arab | Colotis fausta | Maerua oblongifolia |

22. | Tiny grass blue | Zizula hylax | Ruellia patula, R. prostata |

23. | Grass Jewel | Fregyeria putii | Indigofera linnaei, Indigofera cordifolia |

24. | Pea blue | Lempides boeticus | Butea monosperma, Lablab purpureus |

25. | Zebra blue | Leptotes plinius | Plumbago zeylanica, Albizia lebbek |

26. | Gram blue | Euchrysops cnejus | Euchrysops cnejus |

27. | Forget-me-not | Ccotochrysops strabo | Butea monosperma, Tephrosia purpurea |

28. | Striped pierrot | Tarucus nara | Ziziphus mauritiana, Ziziphus nummularia |

29. | Black-spotted pierrot | Tarucus balkanicus | Ziziphus mauritiana |

30. | Common pierrot | Castalius rosimon | Ziziphus mauritiana |

31. | Red pierrot | Talicada nyseus | Bryophyllum pinnatum, Kalanchoe spp. |

32. | Lime blue | Chilades lajus | Citrus limon, Citrus spp. |

33. | Small cupid | Chilades parrhasius | Prosopis cineraria, Acacia leucophloea |

34. | Plains cupid | Chilades pandava | Cycas revoluta |

35. | Indian cupid | Everes lacturnus | Desmodium gangeticum |

36. | Lesser grass blue | Zizina otis | Alysicarpus vaginalis, Desmodium triflorum |

37. | Dark grass blue | Zizeeria karsanadra | Amaranthus viridis, Tribulus terrestris |

38. | Pale grass blue | Pseudozizeeria maha | Oxalis corniculate |

39. | African babul blue | Azanus jesous | Acacia leucophloea |

40. | Bright babul blue | Azanus ubaldus | Acacia nilotica, Acacia leucophloea |

41. | Tailless lineblue | Prosotas dubiosa | Pithecellobium dulce, Prosopis cineraria |

42. | Indian red flash | Rapala airbus | Acacia leucophloea, Butea monosperma |

43. | Common silverline | Spindasis vulcanus | Clerodendrum phlomidis, Ziziphus mauriatiana |

44. | Common shot silverline | Spindasis ictis | Clerodendrum phlomidis, Ziziphus mauriatiana |

45. | Plumbeous silverline | Spindasis schistacea | Acacia spp. |

46. | Common cerulean | Jamides celeno | Pongamia pinnata |

47. | Common guava blue | Virachola Isocrates | Psidium guajava |

48. | Plains blue royal | Tajuria jehana | Dendrophthoe falcata |

49. | Indian sunbeam | Curetis thetis | Pongamia pinnata, Abrus precatorius |

50. | Danaid eggfly | Hypolimans misippus | Portulaca oleracea, Elytraria acaulis |

51. | Great eggfly | Hypolimans bolina | Sida rhombifolia, Rungia spp. |

52. | Blue pansy | Junonia orithya | Lindenbergia muraria, Ruellia prostate |

53. | Lemon pansy | Junonia lemonias | Barleria prionitis, Ruellia tuberosa |

54. | Peacock pansy | Junonia almana | Phyla nodiflora, Hygrophila auriculata |

55. | Yellow pansy | Junonia hierta | Barleria prionitis, Ruellia tuberosa |

56. | Grey pansy | Junonia atlites | Hygrophila auriculata |

57. | Chocolate pansy | Junonia iphita | Barleria cristata |

58. | Painted lady | Vanessa cardui | Echinops echinatus |

59. | Black rajah | Charaxes solon | Tamarindus indicus, Pithecellobium dulce |

60. | Anomalous nawab | Charaxes agrarius | Acacia catechu |

61. | Common evening brown | Melanitis leda | Oryza sativa, Sorghum spp. |

62. | Common three-ring | Ypthima asterope | Cynodon dactylon |

63. | Common four-ring | Papilio demoleus | Cynodon dactylon |

64. | Baronet | Symphaedra nais | Diospyros melanoxylon |

65. | Common sailer | Neptis hylas | Desmodium spp. |

66. | Common castor | Ariadne merione | Ricinus communis, Tragia plukenetii |

67. | Tawany coster | Acraea terpsicore | Passiflora foetida, P. incarnata |

68. | Common leopard | Phalanta phalantha | Flacourtia indica |

69. | Plain tiger | Danaus chrysippus | Calotropis gigantea, Pergularia daemia |

70. | Striped tiger | Danaus genutia | Ceropegia bulbosa |

71. | Common Indian crow | Euploea core | Carissa carandas, Nerium oleander |

72. | Blue tiger | Tirumala limniace | Dregea volubilis |

73. | Indian palm bob | Suastus gremius | Cocos nucifera, Phoenix sylvestris |

74. | Rice swift | Borbo cinnara | Cymbopogen spp., Echinochloa colona |

75. | Small branded swift | Pelopidas mathias | Zea mays, Oryaza sativa |

76. | Swift sp. | Parnara sp. | Setaria spp., Oryaza sativa |

77. | Common banded awl | Hasora chromus | Pongamia pinnata |

78. | Brown awl | Badamia exclamationis | Terminalia bellirica |

79. | Indian skipper | Spialia galba | Waltheria indica, Sida spinosa |

80. | Zebra skipper | Ernsta zebra | Melhania futteyporensis |

81. | Pale palm- dart | Telicota colon | Saccharum officinarum |

82. | Spotted small flat | Sarangesa purendra | Lepidagathis trinervis |

83. | Tricolor pied flat | Coladenia indrani | Mallotus phillipensis |

Many nectar providing species like Adhatoda vasica, Calotropis gigantea, C. procera, Salvia spp., Euphorbia nerifolia, Euphorbia caducifolia, Eharatia laevis, Clerodendron phlamoides, Asclepias curassavica, Buddleia davidii, Vernonia spp., Zinnia spp., Lavender, Marigold, Sunflower, Daisy, Dandelion, Tridex procumbens, Leucas aspera, Anisomeles indica, Leonotis nepetiifolia, Stachytarpheta jamaicensis etc. are also planted in beds and pots to attract the butterflies to feed.

Like butterfly park, other thematic parks like climber park, bush park (shrubbery), euphorbia park, ficus park, ziziphus park, grass park (grassetum), bamboo park (bambusetum), fern park (fernery), rose park (rosery), orchid park (orchidarium) etc. should be developed and maintained regularly for awareness and nature education.

Dr. Satish Kumar Sharma

Assistant Conservator of Forests (Retd.)

14-15, Chakri Amba, Rampura Circle, Jhadol Road

Post – Nai, Udaipur – 313031, Rajasthan

email: sksharma56@gmail.com